Spirogen: The Jewel in the Crown of MedImmune and AstraZeneca

(And why Pfizer will be back)

AstraZeneca hasn’t seen the last of Pfizer which will likely return with another bid in November, after a six month cooling off period. While talks could resume as early as August, at AstraZeneca’s invitation, that’s unlikely to happen.

AstraZeneca rejected Pfizer’s £55 a share (£69 / $118 billion) takeover bid in May saying the offer undervalued the company and its “attractive prospects”. Pfizer’s approach met with opposition from both the political and scientific community, while major investors like BlackRock, Legal & General, Axa and Schroders made it clear they would like the company to engage with Pfizer, which desperately needs to bolster its drug development pipeline and future-proof itself against a possible split into three smaller companies.

Pfizer’s appetite for mergers and acquisitions is well documented. It has to acquire to stay alive. The company is reported to have spent a gargantuan $240 billion on acquisitions since 2000. In that time it bought Warner-Lambert in 2000 ($90 billion), which included Parke-Davis and Wilkinson Sword, Pharmacia in 2002 ($60 billion) which included G.D. Searle and Upjohn, as well as Wyeth in 2009 ($60 billion) and King Pharmaceuticals in 2010 ($3.6 billion). That’s a lot of grist to the mill. Yet Pfizer is now worth $184 billion which serves to highlight the extent of Pfizer’s shareholder value destruction, estimated at $188 billion, between 1993 and 2010.

So why go for AstraZeneca? There are many reasons for Pfizer’s attempted takeover of AstraZeneca but while one is well documented, the other is less so. The most documented reason is for tax purposes; Pfizer wants to buy its Anglo-Swedish rival in part for the financial advantage it would gain by domiciling its holding company in the UK, where the corporate tax rate is lower than in the US. Secondly, Pfizer is desperately looking for drugs to restock its own development pipeline. Combined with the value destruction, Pfizer’s executive must be in a very tight corner indeed. Celebrex, Pfizer’s blockbuster comes off patent this year and Pfizer’s late-stage breast cancer hope, Palbociclib, now looks less promising. But that’s only half the reason.

Pfizer is desperately looking for drugs to fill a serious gap in its own pipeline in the antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) therapeutic class where MedImmune, which AstraZeneca acquired in 2007 for $15.2 billion, proudly sits. With the approval of the drugs Adcetris (Seattle Genetics Inc.) and Kadcyla (Immunogen Inc.), and at least 30 more ADCs in the clinical trial pipeline, the market for this class is expected to grow significantly in future years. More crucially, Mylotarg, Pfizer’s own ADC, was voluntarily withdrawn from the market in 2010 which has left a glaring hole in its portfolio.

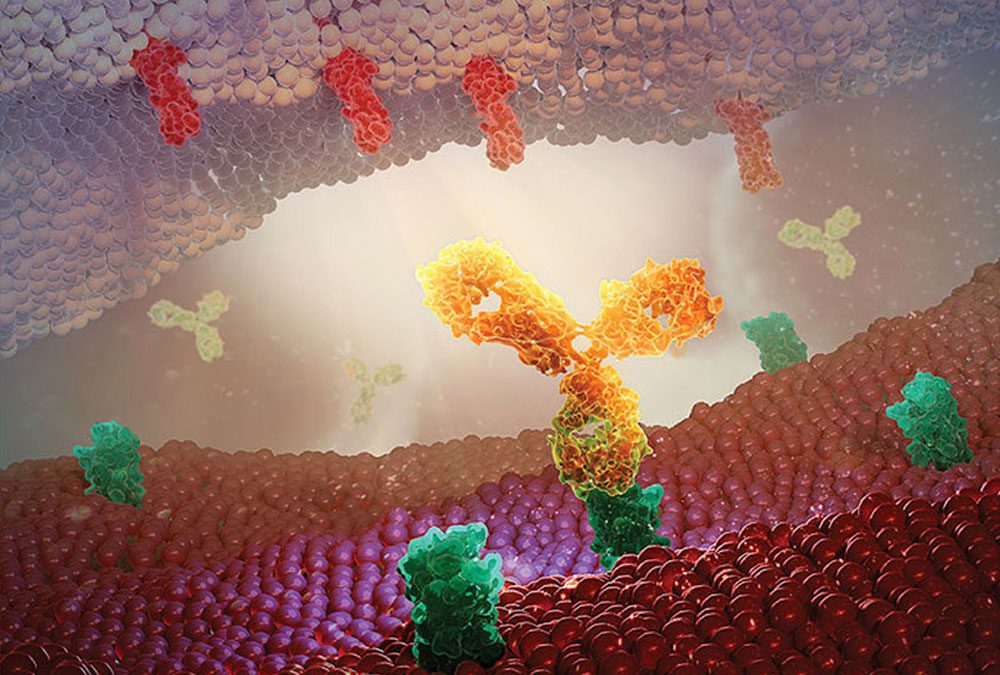

ADCs are monoclonal antibodies conjugated with warheads, loaded with chemotoxins, which seek out specific cancerous cells. The ADC injects the toxins into the infected cell upon contact, killing it while sparing healthy cells nearby. The critical technology is the lysable linker between the two that are engineered to break down cancer cells. The warheads and antibodies are important components but the really subtle stuff is in the linker technology.

For cancer patients, these drugs can dramatically extend lifespan by several hundred days, which is hugely significant compared to the past. And that’s where Spirogen, a tenant at Queen Mary BioEnterprises, comes in. Spirogen, with its antibody warhead technology, was bought by MedImmune for $440 million last year, and is now considered a vital business unit.

So why has Spirogen become so valuable since 2011? This is surely linked to the success of a small Washington-based company that was wrestling for 15 years with patient incremental drug chemistry. Seattle Genetics’ valuation went stratospheric after Adcetris received accelerated FDA approval in August 2011. In a winner takes all race for competitive positioning, these large companies with their armies of business intelligence officers have taken their eyes off the ball and are now having to pay through the nose to catch-up. It’s a cautionary tale which speaks to how big pharma has been wrong-footed time and again in their scramble for new and powerful game-changing technologies. But that won’t put Pfizer off.

AstraZeneca’s Chief Executive, Pascal Soriot, has warned that the takeover could endanger the lives of cancer patients by delaying the development of new drugs. Amid doubts over its motives, the American group’s five-year guarantees on preserving British jobs, which included ensuring that 20% of the research and development workforce stays in the UK, were dismissed by politicians and leading scientists as inadequate. But make no mistake, Pfizer will be back. The capture of these valuable and increasingly sought after ADC assets will drive Pfizer’s future in oncology and there’s a good chance Pfizer will get them, by offering £60 a share.

Note: This article gives the views of the author (Ramsay Richmond) and is not the position of the QMB blog, nor of Queen Mary BioEnterprises, nor of Queen Mary University of London.